The African National Congress (ANC) won a resounding victory in South Africa’s first democratic election in 1994 with a host of promises that it would improve the lives of the Black majority (85% of the population). And whilst there have been gains in some areas, overall, most Black South Africans are materially worse off now than they were under Apartheid.

Hundreds of thousands of jobs have vanished; costs for the basics: electricity, water, food and rents have skyrocketed. Ironically, no longer the pariah of the world, South Africa’s white minority is even better off now than it was under Apartheid (remember the ‘Rainbow Nation’?). The only Blacks to have gained have been a tiny minority, many from the ranks of the (former) liberation movement and the trade unions as well as the South African Communist Party (SACP).

So what went wrong? Did anything go wrong? Has the ANC and its partners in the Tripartite Alliance, the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the SACP betrayed their roots and sold out Black South Africa? Indeed, sold out the rest of Africa?

In the run-up to the 1994 elections, a nationwide debate (of sorts) took place, the outcome of which was a document titled The Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). Yours truly even contributed a paragraph or two on the media, privacy and freedom of information section. It doesn’t advocate a socialist South Africa but it most definitely was the first practical step taken to redress the decades of Apartheid discrimination and repression. This is part of what the document had to say about the importance of the RDP (all the emphases are mine):

1.2 WHY DO WE NEED AN RDP?

1.2.1

Our history has been a bitter one dominated by colonialism, racism, apartheid, sexism and repressive labour policies. The result is that poverty and degradation exist side by side with modern cities and a developed mining, industrial and commercial infrastructure. Our income distribution is racially distorted and ranks as one of the most unequal in the world – lavish wealth and abject poverty characterise our society.

1.2.2

The economy was built on systematically enforced racial division in every sphere of our society. Rural areas have been divided into underdeveloped bantustans and well-developed, white-owned commercial farming areas. Towns and cities have been divided into townships without basic infrastructure for blacks and well-resourced suburbs for whites.

1.2.3

Segregation in education, health, welfare, transport and employment left deep scars of inequality and economic inefficiency. In commerce and industry, very large conglomerates dominated by whites control large parts of the economy. Cheap labour policies and employment segregation concentrated skills in white hands. Our workers are poorly equipped for the rapid changes taking place in the world economy. Small and medium- sized enterprises are underdeveloped, while highly protected industries underinvested in research, development and training.

1.2.4

The result is that in every sphere of our society – economic, social, political, moral, cultural, environmental – South Africans are confronted by serious problems. There is not a single sector of South African society, nor a person living in South Africa, untouched by the ravages of apartheid. Whole regions of our country are now suffering as a direct result of the apartheid policies and their collapse.

1.2.5

In its dying years, apartheid unleashed a vicious wave of violence. Thousands and thousands of people have been brutally killed, maimed, and forced from their homes. Security forces have all too often failed to act to protect people, and have frequently been accused of being implicated in, and even fomenting, this violence.We are close to creating a culture of violence in which no person can feel any sense of security in their person and property. The spectre of poverty and/or violence haunts millions of our people.

There is no doubt that the Apartheid system left behind a gargantuan task for the newly democratized South Africa to overcome. Black ‘education’ was limited to producing ‘hewers of wood and carriers of water’, thus the critical skills and infrastructure needed, especially in governance and education would, even with the best will in the world, take a generation or more to produce if the new South Africa was to redress the imbalances created by white minority rule. White rule that had created an advanced, Western state but for only 5% of the population. A bizarre setup. The only country I know of where there are locks on fridge doors to stop the servants stealing food.

But what became known as Black Economic Empowerment (BEE), was and is largely a bad joke, limited to a tiny black elite who were rapidly coopted into the existing white, capitalist power structures. A process I might add, that had already begun before the 1994 election eg, Cyril Ramaphosa, former head of NUM who became closely involved with the Oppenheimers and the Anglo-American Corporation. (An image sticks in my mind of Ramaphosa, dressed in tweeds and plus fours, fly rod in hand, hanging out with Harry Oppenheimer.)

At this point I should acknowledge that from 1993 through to the election of 1994, I directed the creation of the ANC’s Election Information Unit, tasked with collecting and producing information for the campaign including the ANC’s election programme. Indeed, I occupied a very privileged position to observe the evolution (some might say devolution) of the ANC’s post-Apartheid economic and political programme.

One thing is for sure, at no point did the ANC advocate a socialist alternative in spite of the critical roles both the SACP and COSATU played in the struggle to overthrow Apartheid. Instead, both the SACP and COSATU took a back seat, deferring to the ANC’s neoliberal programme, all in the cause of ‘unity’. The ANC government’s post-Apartheid programme couldn’t even be called a social democratic one, aka postwar Britain’s Labour government. But worse was to come.

The Empire’s neo-liberal agenda

From the end of the 1980s it was clear that Apartheid capitalism’s days were numbered. But it was also the beginning of the end for the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, the ANC’s major backers. The period from around 1988 until the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 was what you might call an interregnum; globally, situations were fluid, many things were possible. In South Africa a window of opportunity existed within which it was possible for progressive forces to gain an advantage. Not necessarily socialism but, as some advocated at the time, progressive structural changes could have been implemented in South Africa that would have been difficult to reverse, had the ANC had the desire to do so.

But from my observations from within the ANC’s election campaign it was clear that Mbeki and those around him had already thrown in their lot, first with Tony Blair’s Labour Party (major advisors in the run-up to the election) and second with Clinton’s Democratic Party. The deal was done. The US even allowed South African communists such as Joe Slovo, formerly branded a terrorist, to visit the US ( I heard him talk at Hunter College in NYC in 1991).

The ANC brought Greenberg-Lake onboard, the US PR company that had engineered Bill Clinton’s successful election campaign, as ‘advisors’ (the ‘Blair-Clinton axis’). Then the US National Democratic Institute (NDI), the Democratic Party’s think-tank tried to get in on the act, quickly followed by the Republican Institute.

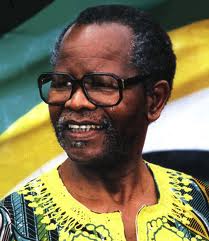

The final (literal) nail in the coffin of a potentially progressive South Africa was the assassination of Chris Hani on the 10 April 1993. Hani, had he lived, in all likelihood would have been the successor to Mandela and South Africa would have had the former Chief of Staff of Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the military arm of the ANC as well as being General-Secretary of the SACP, as president.

Who knows what difference it would have made but Hani was a real hero to the Black masses (anybody who attended the three days of mourning at FNB Stadium in Soweto as I did, will attest to his popularity) and clearly the major reason why he was assassinated. Hani was the last real talent produced by the generation that was led byOR Tambo.

But it was not to be. Global capital would not permit even the taste of a progressive South Africa to come to pass and instead it got ‘their man’ Thabo Mbeki to replace Mandela. Who knows when the ‘deal’ was done but Mbeki, who studied at Sussex University in the UK spent his time in exile embedded in the ANC’s bureaucracy in Lusaka, Zambia, where he kept a low profile. He concentrated on creating a group of cadres close to him, all of whom traveled with him back to South Africa after the ANC was unbanned, and all went on to occupy key positions in both Mandela’s and Mbeki’s government.

I think what has confused many on the left is that the neoliberals within the ANC didn’t get it all their own way, they had to make compromises, especially over the ANC’s foreign policy. For example, on Palestine, Cuba, the invasion of Iraq, the ANC’s foreign policy retained much of its pre-1994 anti-colonialist and anti-imperialist rhetoric and undoubtedly it was the role the SACP played in shaping the ANC’s foreign policy that was the major reason. (A cynic might say that it’s much easier to be a progressive over issues that are not in your own backyard.)

NUM, AMCU, COSATU, SACP, Marikana and the State

The tragedy at Marikana is the logical outcome of the fundamental contradiction that exists when a powerful trade union such as NUM is allied to a political party, the ANC, that is pursuing neoliberal, anti-working class policies. And in turn, because of overlapping memberships and affiliations, the SACP is also complicit in bending reality to fit a very one-sided ‘alliance’.

This incident, as well as others before it in the recent period, should send a very clear message that there is a sustained attack and offensive against COSATU in particular. The SACP has also correctly warned that where our detractors and enemies sense some divisions amongst our ranks, then they always tend to go on the offensive. It might as well be important that these and other related matters needs to be discussed at the COSATU Congress next month, including frank analyses of the strengths and weaknesses of COSATU affiliates as well as some of the threats facing the federation as a whole. This discussion must not take the form of a lamentation or rhetoric, but must aim at concretely coming up with a programme to defend and strengthen COSATU, within the context of deepening the unity of our Alliance. Such a discussion at COSATU Congress must also concretely explore the possible relationship between, Marikana, the current global capitalist crisis, the further decline in the profitability of capitalism, and a renewed offensive to weaken the working class to defend declining levels of profits. — ‘Our condolences and sympathies to the Marikana and Pomeroy Victims’, Blade Nzimande, SACP General Secretary. Umzibenzi Online, Vol. 11, No. 30, 23 August 2012 (my emph. WB)

There’s none so blind as them that won’t see and while it’s true that giant, transnational mining corps do all they can to exploit the contradictions that exist (that’s what capitalists do), it’s still no excuse to talk of “deepening the unity of our Alliance”, as the SACP puts it, when COSATU is de facto complicit in supporting the ANC’s neoliberal policies and all in the name of preserving an alliance that doesn’t actually exist.

NUM’s rival, AMCU is, to put it mildly, a heady mix of tribalism and personal rivalry fueled by a lot of desperate, hungry miners who feel betrayed by NUM and see radical, even violent confrontation with the mine owners/state as the only way to get the gains they justly deserve.

“AMCU was created in 1998 by Joseph Mathunjwa who left the NUM after he fell out with Gwede Mantashe, then general secretary of the older union [NUM].

../

Mantashe by the way, is now Jacob Zuma’s right-hand man and Ramaphosa is on the board of mining giant Lonmin at the centre of the massacre, as are some members of the SACP also now big capitalists. The conflicts of interest abound but this not the important aspect as far as I’m concerned, it’s what underpins it, spelt out by the SACP’s ‘analysis’ above. In 1994 everything changed, except it seems the SACP’s interpretation of the post-Apartheid world when the ANC ceased to be part of the liberation movement after it transformed itself into a political party that followed the Western, capitalist model.

But the ANC succeeded in keeping its liberation period partners onboard, partly because it was a party created in the middle of a struggle for state power with the then Nationalist Party, the party of Apartheid (now folded into the ANC). The ANC needed both its alliance partners onboard if it was to win the struggle with the Nats. After all, such was the following that the SACP had in the townships and COSATU-affiliated unions in the workplace, that they could have called out the masses and taken the transformation down an entirely different path had they chosen to.

Instead, believing itself not strong enough to directly overthrow the Apartheid state (at least that was the public rationale), the ANC struck a deal with the Nats. Called the Sunset Clause and authored by Joe Slovo of the SACP, it was meant to be a temporary power-sharing agreement, designed we were told, to stop a bloodbath from occurring, with Slovo arguing that there was no other choice. Not something everyone agreed with, especially the highly-placed ANC official who leaked the document to the South African Mail & Guardian newspaper (else we would probably never had known it existed). It was also the last time there was any, even reluctant, public debate with the ANC on ANC policies.

It’s difficult to see how the SACP can justify its membership of the Alliance all these years. It’s as if the clock stopped in April 1994 and we are left with the bizarre vision of an SACP justifying its alliance with an ANC which practices neoliberal economic policies, on the basis of preserving unity in the face of a threat, but from what? The remains of an Apartheid state machine, long since incorporated into the ANC, or is it the other way around? In a weird way, it’s a kind of Stalinism but without the socialist bit, illustrated by the fact that we have members of the SACP calling some of its opponents on the left “Anarchists”!

The critical question is how could this have happened in 2012, 18 years into our democracy and the centenary commemoration of the ANC’s struggle for social justice and human dignity?

The answer simply is that there has been a massive failure of leadership on all sides. The critical question is why we did not act earlier on this festering dispute that today the nation mourns?

/../

All they see is the obscenity of shocking wealth and the chasm of inequality growing. The platinum mines they toil in, for a pittance, yield a precious metal that makes exorbitant jewellery that adorns the necks of the affluent and catalytic converters for the expensive cars the middle classes drive. The workers live in hovels, in informal squatter camps, surrounded by poverty and without basic services. All they experience is a political arrogance of leaders who more often than not enrich themselves at the expense [of] the people. They are angry and restless. – Can’t you hear the thunder? By Jay Naidoo, former general secretary of COSATU

Marikana is the rest of South Africa waiting to happen and in large measure it is the result of the SACP’s relationship to the ANC. And being in bed with COSATU compromises the SACP’s independence as much as COSATU compromises its members through its relationship with the ANC. It’s a tangled web we weave, part the product of an era now vanished and part the result of Apartheid capitalism’s perverted vision of reality that has created such a complex set of contradictory relationships. But then again, nobody said that making a revolution was easy.

In South Africa unionised labour constitutes about 10% of those with formal jobs, which ain’t saying much, given as how perhaps as much as 40% of the population are employed in the ‘informal economy’ and thus are not counted or represented by COSATU or the SACP. It’s trade unionism that any old time trade unionist in the UK would recognize, that of industrial capitalism complete with its ‘labour aristocracy’ and yet another depressing legacy of a reformist left, only this time in Africa.

Is it any wonder therefore that the workers at Marikana and elsewhere are turning to a rival and more radical union, AMCU, regardless of the fact that I have some reservations about its motives and its tactics. Will NUM respond to the challenge and return to its roots and defend its members? Or is it too compromised by its connections to the ANC government and to the mining corporations?

By not declaring their political independence from the ANC following the 1994 election, both the SACP and COSATU have, for the past eighteen years effectively blocked the development of an independent and progressive voice on the left, which in turn has let the ANC government rule pretty much with impunity when comes to domestic policies. Unity? But at what cost and to what purpose?

Note

1. Chatterjee’s article supplies a lot of detail about the platinum business and the global recession and subsequent drop in demand for platinum that is actually the current catalyst for the ongoing confrontations between the workers and the mining corporations, of which Marikana is the latest and the bloodiest.

Spaanse Olifantenjager en minnaressenverzamelaar is nu ook Chauffeurmepper

Spaanse Olifantenjager en minnaressenverzamelaar is nu ook Chauffeurmepper